grwm: reflecting on qualitative work in an engineering discipline

me-, method-, methodology

grwm: get ready with me is an internet trend where people walk through how they construct outfits. in this particular flavor of grwm, I walk through the process of writing my most recent paper: ‘Troubling Collaboration: Matters of Care for Visualization Design Study’.

This paper will be presented at CHI 2023, a conference about Human-Computer Interaction. Now that the writing process is complete, I am taking time to reflect on the project and its unexpected challenges and delights.

Paper Summary:

A common research process in visualization is for visualization researchers to collaborate with domain experts to solve particular applied data problems, but there is comparatively little guidance on how to navigate the power dynamics within collaborations.

We interviewed past participants — visualization graduate students, visualization professors, and domain collaborators — in order to better understand how people experience collaboration. We juxtapose the interviewee’s perspectives, revealing tensions about the tools that are built and the relationships that are formed. Then, through the lens of matters of care, we interpret these relationships, concluding with considerations that both trouble and necessitate change in current patterns around collaborative work in visualization design studies.

Our goal with the paper is to share the stories of the participants and spur conversation that will lead to more equitable, useful, and care-ful collaborations.

You can read the paper here: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3544548.3581168 .

Also a quick note, I have chosen to not go into too much detail about the content that appears in the paper for two reasons: 1) I want to keep the blog short and focused on the process and 2) I want to encourage you to read the paper 😈.

Qualitative Analysis takes Time

We spent so much time reading transcripts and sitting with the text. Off the cuff, this is about how much time went into the process of interviewing and analyzing transcripts:

activity x time (hr) = total (hr)

22 interviews x 1 = 22

22 post-interview reflections + discussions x 0.5 = 11

22 transcript corrections x 1.5 = 33

8 transcript analysis sessions x 3 = 24

8 post-analysis reflections x 1 = 8

3 group analysis reflections x 2 = 6

3 group analysis reflections x 2 = 6

1 meeting + discussing index cards x 2 = 2

1 meeting + discussing index cards x 2 = 2

1 meeting + discussing themes x 4 = 4

1 meeting + discussing themes x 4 = 4

Total: 100 hours

And this is not including the time spent on writing and editing which were also critical to the understanding and thinking with and through the text. Granted all research takes time, but a large portion of this project specifically felt like we were trying to learn what to do while we were actually doing it.

And that’s why in our paper, we made it a point to outline our interview and analysis methods as carefully as possible because this type of know-how, techne1, is not abundant in visualization research — a field predominantly focused on statistical or technical ways of reporting.2

Methods

On a very practical level, there were two things that were difficult when it came to reporting on the interviews. The first involved how to quote from audio and the other was how to make sense of the incredibly rich and diverse experiences of our participants.

Quoting Participants

The art of transcription, something I foolishly did not realize until listening and transcribing audio from the interviews, is that it requires a good amount of interpretation. What seems clear and articulate in situ becomes a series of filler words and mumbled phrases, resulting in sentences that are challenging to parse through and understand. With that challenge, I wanted to make sure that I was not “putting words” in the participant’s mouth.

Here are the steps that we followed to ensure participants were accurately represented and readers of the paper could easily read the quoted text.

Initial transcription: The initial “pass” was done through an ML service called Otter.ai. They have a free version, but I opted for the paid product due to the volume of audio we needed to transcribe. The quality of transcriptions was ok. Generally, women and non-native English speakers with heavier accents were translated worse than native English-speaking men. And domain-specific words were also mistranslated.3

Second transcription: I went through the initial transcriptions and corrected the mistakes and anonymized the text.

Interviewee editing: Interviewees were sent the transcript to review. They could add comments or make suggestions for edits. Only 3 (out of 22) participants made edits.

Chunking text for analysis: Another funny thing about talking is that when it is written down it results in large chunks of text. To make it easier to comment on themes in the transcripts, I moved the text files to a spreadsheet and broke the text into smaller chunks, trying to keep related ideas together. Each chunk of text received its own row in the spreadsheet so that when analyzing the transcript, we could drop our comments in adjacent columns.

Reporting on text: Initially, I wanted to include the text as-is when quoted in the paper. But this meant less legibility for readers. I asked friends in the humanities and they said there was no set of agreed-upon principles for how to treat transcript data reporting.4

Tidy-ed quotes: As a compromise between legibility and not-editing the quotes, in the paper, we decided to present “tidy-ed” quotes, removing filler words and editing them for clarity. Pairing the quotes in the paper, we added the original quotes in the supplemental material — so that readers could see the original form of what and how the participant presented an idea.

Diffractive Analysis

Another thing that was surprisingly difficult was reporting on the interesting bits of the interviews. When we did the initial transcript analysis, me, Miriah, and Michael had really interesting discussions. The transcripts sparked us to share our own experiences — externalizing all the ways in which the collaborations that the interviewees spoke of were similar or different to our experiences. However, when we went to discuss this with other team members, the conversation fell flat.

For our initial full-group meeting, I took all the themes from the analysis session and created a Miro board because there was too much material for our colleagues to read through. Those meetings (there were 3 of them) were a total disaster!

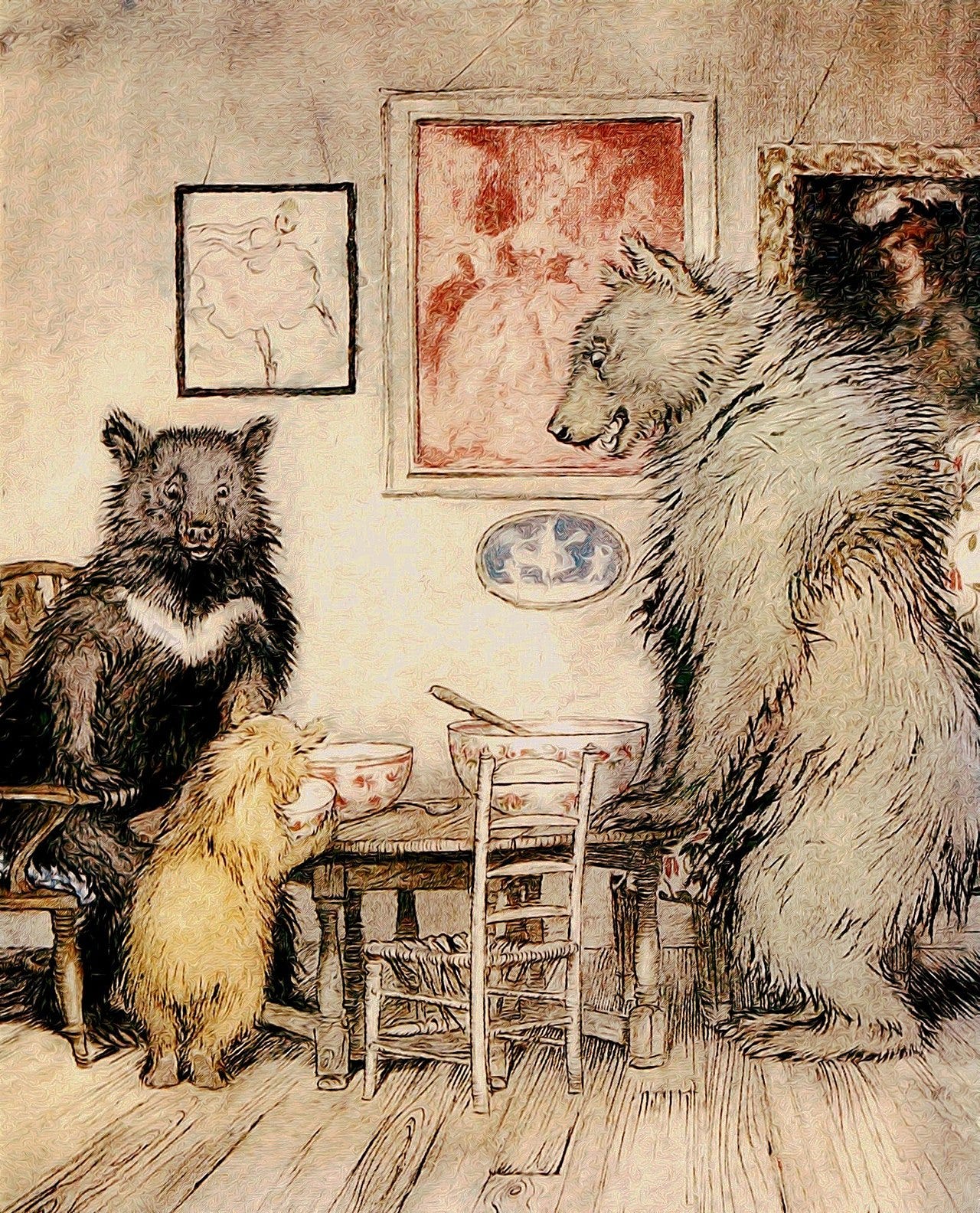

So I went back to the drawing board and came back to the whole group with Golilock’s inspired index cards. The purpose was to provide varying levels of detail about each collaboration.

Each index card provided an overview of the collaboration and then a set of attributes like: unique aspects of the collaborations, views on topic A, decisions regarding topic B, or types of expectations held by interviewees.

Mama Bear Index Card: The mama bear’s porridge was too cold for Goldilocks. In this set of cards, only high-level ideas and bullets were maintained. This document contained the least amount of detail in order to facilitate the fastest read.

Papa Bear Index Card: The papa bear’s porridge was too hot for Goldilocks. In this set, all the details were present. This included high-level ideas, lower-level descriptions, and associated quotes from transcripts. This document was the longest and most detailed.

Baby Bear Index Card: The baby bear’s porridge was just right! In this set, the quotes were removed, and high-level ideas and lower-level descriptions were kept. This set was intended to provide, what I felt, was an appropriate amount of context about the interviews for anyone who did not have the time to read the transcripts.

What we ultimately realized was that the rich details of the interviews in relation to our own experiences are what made the analysis interesting.

We eventually moved toward diffractive analysis as our main methodology for analyzing the transcripts. Instead of reading to find patterns and similarities, we focused on differences that were interesting, and what those differences told us about values and experiences that shaped our participants’ experiences.

I won’t get into too much detail about the diffractive analysis here since we cover it in the paper, but again this methodology does not exist in visualization research so we turned to HCI (Human Computer Interaction) to learn more.5

Discussions with Baggage

Ok. Now it is time to pack our suitcases and take a trip to the land of STS (Science and Technology Studies) and moral philosophy. But as we take this trip you realize that your suitcase is filled with all this other stuff that someone else filled (don’t tell airport security). And it turns out that depending on your destination, that stuff might be unwanted. All of this is to say, we got in some dicey water when it came to how we used matters of care as an analytical lens, especially in conjunction with ethic(s)6. I will share the following thoughts as a summary of the many discussions we had while writing this paper.

Matters of Care + Ethic(s)

Is matters of care an ethical framework?

Ugh, like all things, it depends.

No, it is not an ethics.

This is a position that was supported by an STS colleague, but the reasoning below is mine.

I would argue that Puig de la Bellacasa7 did not intend for matters of care to be applied as an ethics even though she sees care as an ethical concern.

“Caring is more about a transformative ethos than an ethical application. We need to ask ‘how to care’ in each situation. […] It allows approaching the ethicality involved in sociotechnical assemblages in an ordinary and pragmatic way.” (Puig de la Bellacasa, 2011)

Confusing right? In the first sentence, she juxtaposes care with “an ethical application,” which I read as “care is not an ethics.” But then in the third sentence, she states that care is a way to be “ethically involved,” a direct linking of care and ethics. This type of juxtaposition occurs throughout the paper.

A normative definition of ethics relies on universal recommendations on how one is to act. But the ethos of care requires re-considering every interaction, every relationship within its unique and situated context: “Care eschews easy categorization: a way of caring over here could kill over there.” (Puig de la Bellacasa, 2011). So in this way, care does not fit into a prescriptive definition of ethics.

At this point I go down a rabbit hole, wondering if care might be more than virtue ethics (potentially consequentialist) and perhaps this is where the confusion occurs. But I will stop here, recognizing the limits of what I know/don’t know.

Yes, it is an ethics.

There is a Wikipedia page called Ethics of Care, therefore, the answer must be yes. (jokes).

Throughout HCI the term “care ethics” shows up frequently in papers. It even appears in a recent survey paper about the use of ethics in HCI: A Scoping Review of Ethics Across SIGCHI. In this paper, the authors state that care ethics is:

“a philosophical outlook that shifts the moral focus towards embodied, situated and emergent relationships of mutual care, and as such a stark contrast to ethical philosophies centered on principles, norms and duties, such as deontology.” (Vilaza et al., 2022, p. 9, emphasis own)

What fun! We have ended up in the same spot as the previous section, that when comparing care ethics to other ethics, there is clearly a difference. What is unclear though is whether this merits classifying it as an ethic or not.

Is it a lens?

Another debate that took place in writing this paper was the interpretation of how to use the phrase “matters of care.” There were two opinions regarding this:

Matters of Care is in fact a lens

Matters of Care is not a lens but rather a set of things one cares about

As a lens, matters of care is an acute attention to what one cares about and how one cares. So the phrase encompasses both the action and the object of the action. As a not lens, matters of care only delineates what one cares about, therefore it cannot be a lens because it only represents a set of objects of care.

Again, I think both of these perspectives are correct. Interpreting theoretical text is exactly that, an interpretation. There are more popular interpretations and there are less popular interpretations.

Wrapping up…

As the first author, it was my responsibility to understand the competing opinions, interpretations, and perspectives of my co-authors, colleagues, and reviewers. I spent time trying to understand each perspective, and as I said above, I never felt like any interpretation was incorrect, so then it came down to the question of how we could distill the ideas from theoretical text into a cohesive framing within the paper.

Ultimately, two things were important to me:

to follow interpretations that were in line with the broader community’s interpretation, building on prior knowledge rather than proposing a new interpretation of the text

respecting my colleagues and their experience

I felt that if I could balance these two things, then the interpretation of matters of care would support the main message of the paper rather than distract (& piss off) readers. In this moment, the act of stepping back and considering the main goals of the research served as the guiding light.

I hope you enjoyed this flavor of grwm. The goal of this post is to externalize both qualitative methods and work with feminist theory in visualization research so that there is more know-how in the community. If you have any questions, please don’t hesitate to reach out!

Acknowledgements:

Thank you Miriah and the Writing Group at LiU for your feedback and encouragement!

See M. Correll’s paper What Do We Actually Learn from Evaluations in the "Heroic Era" of Visualization? where he makes a different argument about how the VIS community focuses too much on techne and not enough on episteme (“knowing-that”).

My understanding of why this is stems from the field’s historical-intellectual roots as an engineering discipline. As an engineering discipline, it is likely to build more positivist methodologies like stats. This is not to say that the field has ignored qualitative methods, see: S. Carpendale Evaluating Information Visualizations.

Not a domain-specific word, but my name had several amusing transcriptions: dario, derek, jerry, gary, derrius, dairy, & dara.

My concern here was that by editing the text I would impose an opinion of correct dictation.

Turns out it is a nascent methodology in HCI too. We based our diffractive analysis mainly on interpreting Barad’s Diffracting Diffraction: Cutting Together Apart and a recent application of it by Lazar et al. Adopting Diffractive Reading to Advance HCI Research: A Case Study on Technology for Aging.

We also got feedback that we should say ethic instead of ethics for reasons that are still difficult for me to grasp. The literature uses the term “ethics of care” so I will proceed with the plural, but plz send help if you are a moral philosopher or have strong opinions re: ethic v. ethics.

In our paper, we use and interpret Matters of care in technoscience: Assembling neglected things by M. Puig de la Bellacasa. Though C. Gilligan, who is credited as the originator of the term, care ethics, would call it an ethics, see In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development.